Plan for 5-nation force in the Sahel strongly backed by France and Italy but funding resisted by Trump administration

Unprecedented plans to combat human trafficking and terrorism across the Sahel and into Libya will face a major credibility test on Monday when the UN decides whether to back a new proposed five-nation joint security force across the region.

The 5,000-strong army costing $400m in the first year is designed to end growing insecurity, a driving force of migration, and combat endemic people-smuggling that has since 2014 seen 30,000 killed in the Sahara and an estimated 10,000 drowned in the central Mediterranean.

The joint G5 force, due to be fully operational next spring and working across five Sahel states, has the strong backing of France and Italy, but is suffering a massive shortfall in funds, doubts about its mandate and claims that the Sahel region needs better coordinated development aid, and fewer security responses, to combat migration.

The Trump administration, opposed to multilateral initiatives, has so far refused to let the UN back the G5Sahel force with cash. The force commanders claim they need €423m in its first year, but so far only €108m has been raised, almost half from the EU. The British say they support the force in principle, but have offered no funds as yet.

Western diplomats hope the US will provide substantial bilateral funding for the operation, even if they refuse to channel their contribution multilaterally through the UN.

France, with the support of the UN secretary general, António Guterres, and regional African leaders, has been pouring diplomatic resources into persuading a sceptical Trump administration that the UN should financially back the force.

In an attempt to persuade the Americans, Guterres warned in a report to the security council this month that the “region is now trapped in a vicious cycle in which poor political and security governance, combined with chronic poverty and the effects of climate change, has contributed to the spread of insecurity”.

He added: “If the international community stands idly by and does not take urgent action to counter these trends, the stability of the entire region and beyond will be in jeopardy, leaving millions of people at risk of violence, with ordinary civilians paying the heaviest price. Ultimately, the international community will bear the responsibility for such a disastrous scenario.”

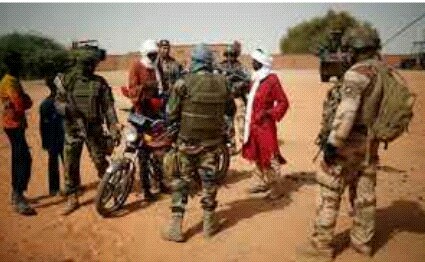

The aim is for the force to be able to combat Islamic terrorism and human traffickers by operating by as much as 50km across state border lines inBurkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger.

Europe’s migration crisis

European powers have a particular interest in changing the dynamic in north Africa, because record levels of migration have overwhelmed southern Europe, divided the EU and polarised politics. This year, the EU has controversially sought to “export” the problem back to north Africa, funding better security in Libya, migrant repatriation and some programs to boost local economies.

This week, the Guardian, in partnership with five other European newspapers – Le Monde, El Pais, La Stampa, Politiken and Der Spiegel – is investigating how the tougher EU approach is affecting migrants and migration routes on Europe’s southern rim.

France – which currently holds the UN rotating presidency and is the former colonial power – is sending its foreign minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, to chair Monday’s UN meeting in New York in a sign of the importance with which Paris regards the initiative and the UN’s backing.

The French president, Emmanuel Macron, visited Bamako, the capital of Mali, in early July and diplomats from the current 15 UN security council states earlier this month were taken to three Sahel countries to gauge the credibility of the plan.

A joint command headquarters has been set up in central Malian town of Sevare, with operations already under way.

Spread across largely difficult desert terrain, the force is due to mount its first operation this month with the initial focus on “taking back control of border areas,” where attacks occur regularly as domestic troops cannot enter another nation’s territory.

Some diplomats believe the deadlyambush of 4 US special forces by Islamist militants in Niger on 4 October has woken the US military to the extent to which countries such as Mali have become the new strategic centres for terrorism.

But Tony Blair, the former UK prime minister, warned Europe not to focus exclusively on the security aspect of the Africa crisis, and the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change has produced a report urging a new plan of action for the Sahel.

Blair told the Guardian: “Security measures will not be enough on their own. Globally a renewed focus must go on uprooting the ideology, while a comprehensive plan of action for the Sahel, which builds institutions and ensures governments in the region can tackle issues of poverty, a lack of jobs and education, must be put in place.

“If the Sahel countries continue in their present state there is a serious risk of new waves of conflict and extremism which will not only threaten those nations but send waves of migration and refugees towards Europe.

“I am proposing a comprehensive plan of action for the Sahel countries which offers them a new partnership to tackle the deep rooted problems of the region including poverty, economic development, lack of institutional capacity, security and of course fighting extremism. The plan should put forward a package of substantial aid and assistance in return for the countries’ agreement to a plan with measurable objectives of change.

“We should try to build an alliance of donor nations willing to contribute to such a plan ideally with European, American and Arab nations in support.”

In an index of the scale of problems facing the five countries, their current population is 78.4 million, expected to increase in 2030 to 118.2 million and by 2050 to 204.6 million, more than 250% growth. Climate change, and the poverty it is likely to induce, the Germany foreign ministry has warned, is likely to become a basis for further Islamist recruitment.

Other critics claim that a UN imprimatur on the G5 Sahel force, given its weak institutional structure, could leave the UN open to charges of overseeing further human rights abuses by UN troops. It is also claimed there is a form of “security traffic jam” in Mali building up. The UN already funds the 11,000 strong MINUSMA anti-terror force – a force that has suffered more than 130 killings since its inception in 2013 and yet failed to prevent a deterioration in security despite a €1bn budget. The French have 4,000 troops in Mali under the banner of Operation Barkhane, while the US are thought to have as many as 900 special forces in Niger.